wilson's petrel off Sheringham and Cley - New to Norfolk

Kevin Shepherd, James McCallum, Richard Millington and Mark Golley

With fresh NNW winds and murky conditions forecast, several north coast birders were out seawatching early on 23rd July 2010 when a remarkable team effort secured a most unexpected addition to the county list. This article is based on extracts of the detailed accounts received from some of the observers involved.

Kevin Shepherd was first to see the bird, as he describes:

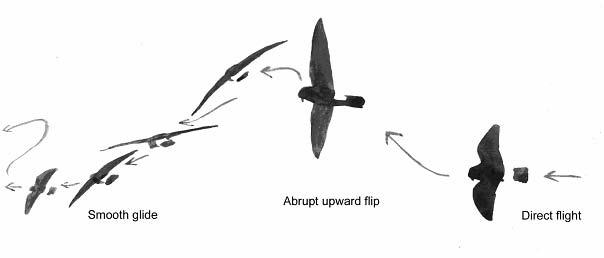

"I had made my usual pre-dawn (4.20 am) start at ‘The Leas’, Sheringham and enjoyed an excellent passage of 450+ Gannets and 500+ Sandwich Terns east during the first two hours. With such a volume of birds on the move, at a perfect time of year and in excellent conditions for one, I was carefully seeking a late-summer Storm Petrel when my efforts were suddenly rewarded with a petrel sp. out to the northeast, moving west. Engaged in steady, fast-flapping, direct flight low over the sea, too small and with wings too short for Leach’s, I naturally assumed it was indeed a Storm Petrel, and relaxed to enjoy the bird as it continued its steady approach. It was soon met by two relatively large ‘green’ waves and, as would have been typical for Storm, took the first completely in its stride as if it wasn’t there, steadily beating up the wave’s face to fly over the top. However, when it reached the very top, it suddenly did something completely unexpected and uncharacteristic of Storm - for no apparent need or reason, it suddenly sheared up (belly into the wind), then made a prolonged glide along the wave’s face and into the trough ahead of the same wave, its then immediate return to steady flapping with gathered speed then successfully taking it over the same wave. In addition, particularly as it sheared, but also as it then glided, its wings suddenly didn’t look so small after all. Instead they were slightly longer, and obviously much broader than I had previously imagined, suddenly conveying an overall ‘jizz’ and structure most unlike Storm. Briefly revealing its entire upperside in plan view during its first shear, it also seemed to show quite a noticeable broad pale upperwing-covert bar.

Before I had time to properly process my thoughts, it was beating up the face of the second wave towards its top to deal with it in exactly the same way as the first. My now much more intense focus on its second shear and prolonged glide confirmed all earlier impressions. The whole bird was also now fairly obviously not ‘tiny’ like Storm at all - it was bigger, though certainly not as big or long-winged as Leach’s. From the start it was obviously not a Leach’s Petrel. Yikes! Now it was obviously not a Storm Petrel either!! Suppressing all excitement, it was time for calm and careful observation, when it was easy to confirm on several occasions that there was clearly no white on the underwing (given identical viewing conditions and range, white on the underwing of a Storm Petrel would have been clearly visible). The ‘rump’ (actually the uppertail coverts) was clearly very obvious and pure white throughout and also obviously ‘wrapped around’ to extend well on to the underside (though it was very difficult to be sure exactly how far it extended). Unfortunately, the bird was too far out to be able to discern any fine detail such as toes projecting beyond the tail. Knowing that Madeiran was a relatively large, long-winged, very Leach’s-like petrel (which this very obviously wasn’t), the bird was presumably a Wilson’s - but with no previous experience of this ‘difficult’ species, how could I be sure? Help was urgently required so, with the bird now obviously gone west, I simply dumped all my optical equipment and sprinted to the cliff-top to obtain a mobile signal, to try to alert the seawatchers at Cley that a very interesting petrel was heading their way....."

With fresh NNW winds and murky conditions forecast, several north coast birders were out seawatching early on 23rd July 2010 when a remarkable team effort secured a most unexpected addition to the county list. This article is based on extracts of the detailed accounts received from some of the observers involved.

Kevin Shepherd was first to see the bird, as he describes:

"I had made my usual pre-dawn (4.20 am) start at ‘The Leas’, Sheringham and enjoyed an excellent passage of 450+ Gannets and 500+ Sandwich Terns east during the first two hours. With such a volume of birds on the move, at a perfect time of year and in excellent conditions for one, I was carefully seeking a late-summer Storm Petrel when my efforts were suddenly rewarded with a petrel sp. out to the northeast, moving west. Engaged in steady, fast-flapping, direct flight low over the sea, too small and with wings too short for Leach’s, I naturally assumed it was indeed a Storm Petrel, and relaxed to enjoy the bird as it continued its steady approach. It was soon met by two relatively large ‘green’ waves and, as would have been typical for Storm, took the first completely in its stride as if it wasn’t there, steadily beating up the wave’s face to fly over the top. However, when it reached the very top, it suddenly did something completely unexpected and uncharacteristic of Storm - for no apparent need or reason, it suddenly sheared up (belly into the wind), then made a prolonged glide along the wave’s face and into the trough ahead of the same wave, its then immediate return to steady flapping with gathered speed then successfully taking it over the same wave. In addition, particularly as it sheared, but also as it then glided, its wings suddenly didn’t look so small after all. Instead they were slightly longer, and obviously much broader than I had previously imagined, suddenly conveying an overall ‘jizz’ and structure most unlike Storm. Briefly revealing its entire upperside in plan view during its first shear, it also seemed to show quite a noticeable broad pale upperwing-covert bar.

Before I had time to properly process my thoughts, it was beating up the face of the second wave towards its top to deal with it in exactly the same way as the first. My now much more intense focus on its second shear and prolonged glide confirmed all earlier impressions. The whole bird was also now fairly obviously not ‘tiny’ like Storm at all - it was bigger, though certainly not as big or long-winged as Leach’s. From the start it was obviously not a Leach’s Petrel. Yikes! Now it was obviously not a Storm Petrel either!! Suppressing all excitement, it was time for calm and careful observation, when it was easy to confirm on several occasions that there was clearly no white on the underwing (given identical viewing conditions and range, white on the underwing of a Storm Petrel would have been clearly visible). The ‘rump’ (actually the uppertail coverts) was clearly very obvious and pure white throughout and also obviously ‘wrapped around’ to extend well on to the underside (though it was very difficult to be sure exactly how far it extended). Unfortunately, the bird was too far out to be able to discern any fine detail such as toes projecting beyond the tail. Knowing that Madeiran was a relatively large, long-winged, very Leach’s-like petrel (which this very obviously wasn’t), the bird was presumably a Wilson’s - but with no previous experience of this ‘difficult’ species, how could I be sure? Help was urgently required so, with the bird now obviously gone west, I simply dumped all my optical equipment and sprinted to the cliff-top to obtain a mobile signal, to try to alert the seawatchers at Cley that a very interesting petrel was heading their way....."

To the west, at Cley, James McCallum and Richard Millington were in situ at the beach shelter. The following extract from James’s description continues the story:

“I arrived at Cley beach to find Richard already present. He had seen a few Manx Shearwaters so I decided to join him for a while. The totals of seabirds moving were not great but I did manage to see a few Manx Shearwaters and small numbers of Gannets. All too soon the passage began to ease and I was thinking of leaving when Richard received a call from home: it was Hazel passing on the message that ‘Kevin Shepherd had seen, about ten minutes ago, a petrel moving west past Sheringham that wasn’t a Leach’s’. Being a bit ‘slow’ that morning I didn’t really grasp what that implied, but thought the chance of seeing any petrel on a relatively flat sea was worth waiting for. By pure coincidence, Dave Holman, Christine Stean and Baz Harding arrived at about this time, as did Mark Golley on his clockwise tour of the reserve and Trevor Davies on his pre-work, anticlockwise route. With a petrel potentially on its way, everyone scanned the sea for it. After 15 minutes some were suggesting that we had already missed it or it had moved out to sea but I remembered that seabirds had, at times, taken a surprisingly long period of time to travel between these sites so I remained focused. After half-an-hour I think everybody was pessimistic and after 45 minutes most were thinking of leaving as there were virtually no other seabirds moving. People stopped looking so intently and started chatting and I joked that I was still ‘very optimistic and tingling with excitement’. In reality I too was on the verge of folding up my tripod and leaving. Then, to my amazement, a petrel suddenly flipped up into my view! It then glided into a wave trough and, without flapping, flipped up over a wave crest then continued its glide. The flight-mode was very interesting and I called out ‘petrel’, much to everyone’s surprise. Unfortunately, in the ensuing panic my tripod got kicked so I instantly lost the bird! Being used to the choice of two species of petrel on a typical Norfolk seawatch my initial thought at this stage was, contrary to Kevin’s thoughts, that the bird was flying in an accomplished and exciting manner that seemed much more reminiscent of a Leach’s than a Storm Petrel. Fortunately the petrel was still a good way to the east when Richard picked it up again and everyone was quickly able to get on it. Seeing it again, I was surprised to see that its flight had changed and it was flying directly with fairly rapid wingbeats just above the surface of the sea - a flight action I associated more with Storm Petrel than Leach’s. The bird, however, looked distinctly bigger than a Storm Petrel and furthermore its overall shape and extensive, square-edged and gleaming white rump instantly ruled Leach’s out of the equation. The petrel then flipped up abruptly at c90° to the sea before performing a smooth shallow glide downwards on flat wings, a flight action that was quickly repeated. This action, however, wasn’t reminiscent of Storm Petrel. This was quickly proving to be a very interesting bird!”

Everybody present was able to get on the bird and although most of the observation was made in silent concentration there was an atmosphere of intense excitement. Richard’s notes describe the appearance of the bird and the next sequence of events:

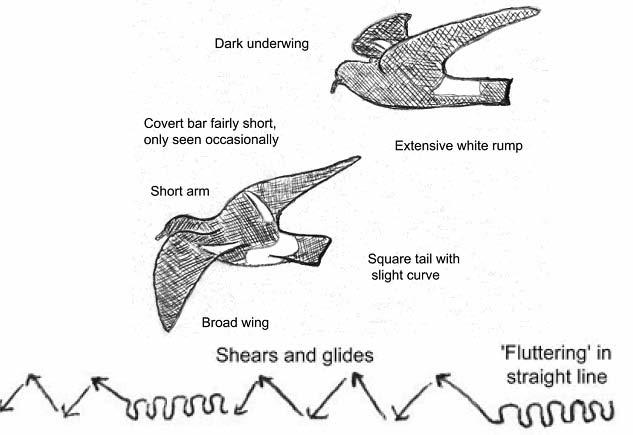

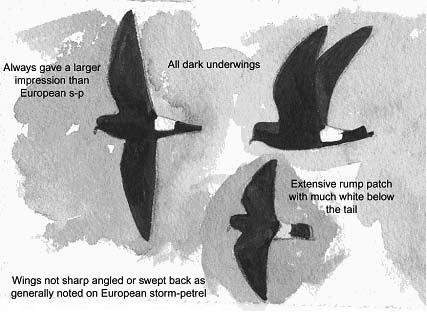

“My initial views were of the bird side-on. Although it was continuously flapping, in these profile views I was struck by the rather elongated-looking rear-end. In relation to the rest of the bird, this looked somehow narrower than usual too. It then swooped and briefly sheared on outstretched wings. It showed a rather bow-shaped wing and a short ‘arm’ but long ‘hand’; the forewing profile was bulging and evenly rounded at the elbow but the hindwing was rather straight-edged. In addition, a short pale carpal bar was visible on the upper innerwing. Thus I voiced that the bird was ‘looking good for Wilson’s’. The bird then continued in a straight line with a continuous flapping action, and talk turned to that action surely being a Storm Petrel trait. However, although a ‘wrap-around’ white rump was visible (the white reaching below the level of the tail), there was no hint of the pale underwing bar that would be expected (and that surely would have been visible given the conditions) on Storm Petrel. Throughout the whole viewing, no white was seen on the underwing, so it really had to be absent. Although the fast wing-beats were disconcerting, the bird lacked the busy, scurrying, bustling flight of Storm Petrel, nor did it hold its wings angled and it never had that squat, short-bodied look. Indeed, with the next bout of shearing glides the impression that it was a larger, more leisurely petrel than a Storm was taking shape and the realisation that this was neither a Storm nor a Leach’s Petrel was firming up. Fortunately, as the bird progressed further west, veering further out and then closer in again, it indulged in far more banking and gliding. By now, straight-winged slip-shearing was the predominant mode of flight, effectively eliminating Storm Petrel. At this range, a more Leach’s-like impression was gained, even though the size and wing-shape never approached that species. The bird was now side-sweeping waves with ease and no longer were the fluttering wing-beats of the earlier, more direct flight spells being utilised.”

“I arrived at Cley beach to find Richard already present. He had seen a few Manx Shearwaters so I decided to join him for a while. The totals of seabirds moving were not great but I did manage to see a few Manx Shearwaters and small numbers of Gannets. All too soon the passage began to ease and I was thinking of leaving when Richard received a call from home: it was Hazel passing on the message that ‘Kevin Shepherd had seen, about ten minutes ago, a petrel moving west past Sheringham that wasn’t a Leach’s’. Being a bit ‘slow’ that morning I didn’t really grasp what that implied, but thought the chance of seeing any petrel on a relatively flat sea was worth waiting for. By pure coincidence, Dave Holman, Christine Stean and Baz Harding arrived at about this time, as did Mark Golley on his clockwise tour of the reserve and Trevor Davies on his pre-work, anticlockwise route. With a petrel potentially on its way, everyone scanned the sea for it. After 15 minutes some were suggesting that we had already missed it or it had moved out to sea but I remembered that seabirds had, at times, taken a surprisingly long period of time to travel between these sites so I remained focused. After half-an-hour I think everybody was pessimistic and after 45 minutes most were thinking of leaving as there were virtually no other seabirds moving. People stopped looking so intently and started chatting and I joked that I was still ‘very optimistic and tingling with excitement’. In reality I too was on the verge of folding up my tripod and leaving. Then, to my amazement, a petrel suddenly flipped up into my view! It then glided into a wave trough and, without flapping, flipped up over a wave crest then continued its glide. The flight-mode was very interesting and I called out ‘petrel’, much to everyone’s surprise. Unfortunately, in the ensuing panic my tripod got kicked so I instantly lost the bird! Being used to the choice of two species of petrel on a typical Norfolk seawatch my initial thought at this stage was, contrary to Kevin’s thoughts, that the bird was flying in an accomplished and exciting manner that seemed much more reminiscent of a Leach’s than a Storm Petrel. Fortunately the petrel was still a good way to the east when Richard picked it up again and everyone was quickly able to get on it. Seeing it again, I was surprised to see that its flight had changed and it was flying directly with fairly rapid wingbeats just above the surface of the sea - a flight action I associated more with Storm Petrel than Leach’s. The bird, however, looked distinctly bigger than a Storm Petrel and furthermore its overall shape and extensive, square-edged and gleaming white rump instantly ruled Leach’s out of the equation. The petrel then flipped up abruptly at c90° to the sea before performing a smooth shallow glide downwards on flat wings, a flight action that was quickly repeated. This action, however, wasn’t reminiscent of Storm Petrel. This was quickly proving to be a very interesting bird!”

Everybody present was able to get on the bird and although most of the observation was made in silent concentration there was an atmosphere of intense excitement. Richard’s notes describe the appearance of the bird and the next sequence of events:

“My initial views were of the bird side-on. Although it was continuously flapping, in these profile views I was struck by the rather elongated-looking rear-end. In relation to the rest of the bird, this looked somehow narrower than usual too. It then swooped and briefly sheared on outstretched wings. It showed a rather bow-shaped wing and a short ‘arm’ but long ‘hand’; the forewing profile was bulging and evenly rounded at the elbow but the hindwing was rather straight-edged. In addition, a short pale carpal bar was visible on the upper innerwing. Thus I voiced that the bird was ‘looking good for Wilson’s’. The bird then continued in a straight line with a continuous flapping action, and talk turned to that action surely being a Storm Petrel trait. However, although a ‘wrap-around’ white rump was visible (the white reaching below the level of the tail), there was no hint of the pale underwing bar that would be expected (and that surely would have been visible given the conditions) on Storm Petrel. Throughout the whole viewing, no white was seen on the underwing, so it really had to be absent. Although the fast wing-beats were disconcerting, the bird lacked the busy, scurrying, bustling flight of Storm Petrel, nor did it hold its wings angled and it never had that squat, short-bodied look. Indeed, with the next bout of shearing glides the impression that it was a larger, more leisurely petrel than a Storm was taking shape and the realisation that this was neither a Storm nor a Leach’s Petrel was firming up. Fortunately, as the bird progressed further west, veering further out and then closer in again, it indulged in far more banking and gliding. By now, straight-winged slip-shearing was the predominant mode of flight, effectively eliminating Storm Petrel. At this range, a more Leach’s-like impression was gained, even though the size and wing-shape never approached that species. The bird was now side-sweeping waves with ease and no longer were the fluttering wing-beats of the earlier, more direct flight spells being utilised.”

After the bird was lost to sight, the atmosphere of intense concentration turned to one of shock, for all present knew that they had witnessed something special. Naturally, much conversation followed, everybody agreeing that the bird was obviously not a Leach’s or Storm Petrel. The age-old choice of two species of petrel on a Norfolk seawatch was suddenly obsolete! From whatever angle the observation was looked at, Wilson’s Petrel was the only possibility!

Most of the observers had previous experience of Wilson’s Petrel and all agreed that the plumage was consistent with their experience of the species. The aspect of the bird that generated some confusion was, however, its flight mode. The majority of observers with past experience felt that the flight was close to their previous experience. For example, Mark states in his description:

“My most recent encounter with the species came less than two weeks before the Cley bird. While working at the World Cup in South Africa, I managed to take a place on a pelagic that headed some 20 miles off Cape Point and amongst all the albatrosses, Sooty Shearwaters, Kelp Gulls and skuas, I was able to watch at least 20-30 Wilson’s Petrels at close to moderate range, off and on, for at least two hours. Plumage details aside, the most pleasing aspect of the sighting on 23rd July was the near-identical flight pattern shown by the birds in South Africa and the individual off Cley - the characteristic swift transit across the sea on rapid wing-beats, coupled with numerous shears and glides was just the same, despite there being several thousand miles between the sightings.”

Richard shared a similar view:

“I have had experience previously with Wilson’s Petrel in two different ways. Initially, the famous St. Ives bird of 3rd September 1983, watched mostly from directly above, its main identification feature being the double row of circular concentric waves it left behind as it hopped along, dipping both of its feet into the calm water! More recently, I’ve been with Killian Mullarney at Bridges of Ross when he’s picked up Wilson’s Petrels flying by in windy conditions ... but on every one of the three occasions I had trouble convincing myself that I could really eliminate Storm until the point at which each bird began to swoop left and away. The Cley event closely recalled the latter experiences, but there was one major difference - Wilson’s Petrel occurs regularly off western Ireland … in the North Sea it does not!”

However, for others the flight of the Cley bird did not comfortably fit their past experience of the species. In his description James explains his confusion:

“Just the previous August I had my first encounters with Wilson’s Petrel from boats off the Isles of Scilly. At least eleven birds were seen over three days. Two weeks later I was really fortunate to see two birds from a land-based seawatch from Pendeen in Cornwall. The two Wilson’s seen in a seawatch context I naturally assumed would be most relevant when comparing the bird seen off Cley. Both the Pendeen birds I picked up due to their distinctive flight. The first bird was slightly closer than the Cley petrel and, although initially flapping, it then began an amazing prolonged glide on slightly depressed wings before stopping to ‘dance’ over the surface then simply glided off. It hardly flapped at all until I lost it in the rough sea. The second bird was slightly further out - probably at a similar range to the Cley bird. This bird was first seen continually ‘bouncing’ over the same area of sea for about a full minute! It then glided in the same way as the first before rapidly fluttering off. Looking back I actually saw the covert bar of the first bird once, clearly, if only very briefly when it was gliding and not at all on the second bird. However, the flight mode of those two birds was very different to that of the Cley bird.”

Puzzled by these conflicting experiences of the flight action of Wilson’s Petrels, James decided to contact Bob Flood who kindly read through his account of the Cley bird and gave the following reply:

“I just read through your description of the Norfolk Wilson’s. I can appreciate your frustration. It is easy to get muddled over flight behaviour unless it is understood that there are three main types: travelling, foraging and collecting. Much of what we saw off Scilly was foraging and collecting - foraging with hirundine-like flight and collecting by snatching off the surface as the Wilson’s kept going, or collecting by dancing. Your Pendeen Wilson’s were also foraging and collecting. The Norfolk Wilson’s, by your account, was in travelling flight. Travelling flight of Wilson’s is different. The following account of travelling flight of Wilson’s is taken from the forthcoming DVD-book set ‘Storm-petrels & Bulwer’s Petrel’: ‘Travelling flight: Purposeful and fairly direct, frequently glides; wing beats stiff, fast, and shallow. In relaxed traveling flight, it often glides and veers from side-to-side, reminiscent of a Barn Swallow. It regularly shears short distances in moderate to strong winds.’

Your description of the travelling flight behaviour of the Norfolk bird is good for Wilson’s. The amount of gliding and shearing by the Norfolk bird is excessive for Storm Petrel.”

With Bob Flood’s short but precise explanation the confusion instantly subsided and, at last, everyone could fully enjoy this exciting record. With warming seas, better optics and a more open-minded approach to seawatching, further North Sea records of Wilson’s Petrels are sure to follow. Clearly we no longer have the familiar choice of just two species of ‘black-and-white’ petrel on future Norfolk seawatches!

“My most recent encounter with the species came less than two weeks before the Cley bird. While working at the World Cup in South Africa, I managed to take a place on a pelagic that headed some 20 miles off Cape Point and amongst all the albatrosses, Sooty Shearwaters, Kelp Gulls and skuas, I was able to watch at least 20-30 Wilson’s Petrels at close to moderate range, off and on, for at least two hours. Plumage details aside, the most pleasing aspect of the sighting on 23rd July was the near-identical flight pattern shown by the birds in South Africa and the individual off Cley - the characteristic swift transit across the sea on rapid wing-beats, coupled with numerous shears and glides was just the same, despite there being several thousand miles between the sightings.”

Richard shared a similar view:

“I have had experience previously with Wilson’s Petrel in two different ways. Initially, the famous St. Ives bird of 3rd September 1983, watched mostly from directly above, its main identification feature being the double row of circular concentric waves it left behind as it hopped along, dipping both of its feet into the calm water! More recently, I’ve been with Killian Mullarney at Bridges of Ross when he’s picked up Wilson’s Petrels flying by in windy conditions ... but on every one of the three occasions I had trouble convincing myself that I could really eliminate Storm until the point at which each bird began to swoop left and away. The Cley event closely recalled the latter experiences, but there was one major difference - Wilson’s Petrel occurs regularly off western Ireland … in the North Sea it does not!”

However, for others the flight of the Cley bird did not comfortably fit their past experience of the species. In his description James explains his confusion:

“Just the previous August I had my first encounters with Wilson’s Petrel from boats off the Isles of Scilly. At least eleven birds were seen over three days. Two weeks later I was really fortunate to see two birds from a land-based seawatch from Pendeen in Cornwall. The two Wilson’s seen in a seawatch context I naturally assumed would be most relevant when comparing the bird seen off Cley. Both the Pendeen birds I picked up due to their distinctive flight. The first bird was slightly closer than the Cley petrel and, although initially flapping, it then began an amazing prolonged glide on slightly depressed wings before stopping to ‘dance’ over the surface then simply glided off. It hardly flapped at all until I lost it in the rough sea. The second bird was slightly further out - probably at a similar range to the Cley bird. This bird was first seen continually ‘bouncing’ over the same area of sea for about a full minute! It then glided in the same way as the first before rapidly fluttering off. Looking back I actually saw the covert bar of the first bird once, clearly, if only very briefly when it was gliding and not at all on the second bird. However, the flight mode of those two birds was very different to that of the Cley bird.”

Puzzled by these conflicting experiences of the flight action of Wilson’s Petrels, James decided to contact Bob Flood who kindly read through his account of the Cley bird and gave the following reply:

“I just read through your description of the Norfolk Wilson’s. I can appreciate your frustration. It is easy to get muddled over flight behaviour unless it is understood that there are three main types: travelling, foraging and collecting. Much of what we saw off Scilly was foraging and collecting - foraging with hirundine-like flight and collecting by snatching off the surface as the Wilson’s kept going, or collecting by dancing. Your Pendeen Wilson’s were also foraging and collecting. The Norfolk Wilson’s, by your account, was in travelling flight. Travelling flight of Wilson’s is different. The following account of travelling flight of Wilson’s is taken from the forthcoming DVD-book set ‘Storm-petrels & Bulwer’s Petrel’: ‘Travelling flight: Purposeful and fairly direct, frequently glides; wing beats stiff, fast, and shallow. In relaxed traveling flight, it often glides and veers from side-to-side, reminiscent of a Barn Swallow. It regularly shears short distances in moderate to strong winds.’

Your description of the travelling flight behaviour of the Norfolk bird is good for Wilson’s. The amount of gliding and shearing by the Norfolk bird is excessive for Storm Petrel.”

With Bob Flood’s short but precise explanation the confusion instantly subsided and, at last, everyone could fully enjoy this exciting record. With warming seas, better optics and a more open-minded approach to seawatching, further North Sea records of Wilson’s Petrels are sure to follow. Clearly we no longer have the familiar choice of just two species of ‘black-and-white’ petrel on future Norfolk seawatches!